“The only thing I’m worried about is the sewage from the next car.”

About 40 minutes into a 17-hour train ride, this is the last thing you want to hear from Amtrak personnel. Thursday, I took a seat in a coach car of the 5:20

Capital Limited bound for Chicago, near one of the doors linking two double-decker coach cars. And that door was broken.

It was a semi-automatic door. If it had worked properly, you would have pressed a panel (similar to those on newer London Underground trains), the door slides open and after a few moments, it closes again.

This door refused to open like it should (it had to be slid with a little bit of force) and it didn’t shut on its own, leaving the ever-moving and jostling crossover passage open to our car. Along with the noise, it also let in smells.

The sewage warning came from Candice, the Capitol Limited’s dinner reservationist, who was going through the train car booking people for dinner. (I really don’t know what her name was; Candice seems appropriate.) While the couple across the aisle from me was interested in booking a table for their evening meal, they asked Candice whether anything could be done about the door.

“Sir, I can’t hear you!” Candice said in reply to the man’s question about the door.

“Can anything be done about the door?” he asked again, trying to elevate his voice above the clamor from the passageway.

Candice leaned over. “Sir, I can’t hear you,” she repeated pointing to the door.

“I know …”

“What?”

“The door. We can’t hear anything because of the door,” he said, his voice elevated and annoyed.

“Oh, the door. Yeah I think it’s broken.” Candice said.

Well it was broken and the couple was not pleased.

“Perhaps you can smell the raw sewage now,” Candice, flaring her nostrils, told the couple, an older duo in their late 50s. Her concern was that sewage from the next car would come into our car via wafty breezes generated in the open passage. Apparently, from what she said, the smell would be worse while going through musty damp tunnels of western Maryland and southwest Pennsylvania.

“There isn’t a maintenance man on board. You may want to talk to your attendant about moving.”

“You mean that nothing can be done with the door?” the man asked.

“Naaah, not really, not until Chicago. I’ll see what I can do … Anyone else want a reservation for the dining car?” Candice moved on with her duties. The door wasn’t her concern.

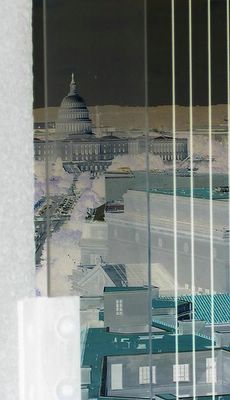

And so began the first leg on my trip to Michigan. The overnight Capital Limited would get me to Chicago, where my parents would pick me up and take me home to Michigan for a few days escape from Washington. But that was six more states away.

Watching Door No. 31543. I could have moved seats. But I decided to stay by the door. The noise wasn’t that unbearable. I thought it would be an interesting observational study of human behavior. To what degree would the door annoy the passengers around me? Would the crew actually do their all to fix it, or make the situation better? With the prospect of the situation not improving, how long would it take for the annoyance to grind away at the civility of our train car?

Not that long.

On the way out of Montgomery County, the couple closest to the door did their best to close it when people were passing through. In fact there was applause when the first person managed to open it, and then pull at the rubber seal inside the door’s slider unit to close it. There was actual glee when that happened.

Then a younger couple in their 30s made their way through. They managed to open the door, but didn’t even think about the possibility that it wouldn’t close. Why would they anyway?

As the younger woman walked by, the woman in the seat across the aisle from me (let’s call her Millie) said, “We’d like that closed,” pointing to the door. “It doesn’t shut, you see?”

The younger woman, her skin stretched and parched by years of cigarette smoking, was taken by surprise and was annoyed. As instructed by Millie, she returned to the doorway, with her boyfriend or hubby, Jim, in tow.

Jim tried to fix the door, with instructions from the peanut gallery.

“You have to pull on it, from the …” Millie yelled across a few seats.

Millie’s husband said, to add some comic relief: “That’s they way we did it in 1895.”

He laughed at his comment. But the younger woman, wearing a Cleveland Indians baseball cap and annoyed that they were tasked with fixing the door, said “C’mon Jim, let the woman fix it,” referring to Millie.

It seems like she was in need of a cigarette.

The young couple’s escape from the door quandary was aided by Joe, the overly rotund Amtrak attendant, who was doing his rounds in the car, what ever those were. The door wasn’t at the top of his list.

But to be polite, he tried to fiddle with some door key gizmo that switched the door from automatic to manual. There was confusion between Millie and Joe.

“I can’t do it manually,” Joe said.

“Yes, you can see that we’ve been closing it,” Millie said.

“With the open position, I can’t guarantee it’s going to remain closed,” Joe said trying to explain the intricacies of the door unit. When asked if a sign could be placed there, he said he’d do that. But he never did put a sign up, and when he moved through the car on the rest of the trip to Chicago, he never bothered to shut it behind him. We gave up on Candice doing anything, now we gave up on Joe. The annoying door would remain annoying.

If Virginia Is for Lovers, West Virginia Is for Trainspotters. As the Capital Limited pushed along toward the Mountain State, the door problems remained. People had some trouble opening the door, others found it real easy.

A young mother who was holding her child way up on her shoulder -- which looked like it was only a couple weeks old -- tried to figure out the door. It was a tricky balance. And the best she could do was hit the door button. Repeatedly. But to no avail the door could not open by simply hitting it. If she had tried to use her force to slide the door open, she risked dropping her child.

Then Candice came through to rescue. It wasn’t that she saw the mother in need of assistance, she just happened to be passing through announcing that that those passengers with 6:15 dinner reservations should make their way to the dining car for their on-board prepared choice-cut steaks, ravioli primavera and stuffed peppers.

Candice moved on, and the door remained open and I could see the train cars jostle about as they moved along the hilly curves of the Appalachian foothills. As the train moved on its way from Point of Rocks, Md., along the wooded bluffs of the Potomac’s north bank, I got my first whiff of what Candice warned was coming. Imagine three-day’s old garbage, tinged with vinegar and accents of a roadside rest area plagued by state budget cuts. It wasn’t overpowering by any means, but it was there, reminding you that everyone in the world has bowel movements.

The smell started to go away when the train slowed down slightly going past a backwater rail yard where trains for MARC’s Brunswick Line are stored. There were a number of train cars, spattered with graffiti, sitting idly by in the far-off wooded train yard. As the train moved though a series of tunnels in the vicinity of Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., wafts of sewage came in.

Soon we crossed an old railroad bridge across the Potomac into Harper’s Ferry, the small junction where John Brown’s 1859 failed slave insurrection came to an end. The train stopped at the station and we were greeted with a bunch of photographers taking photos of our Amtrak Superliner.

In a few moments, the train pulled out from the ancient station. Was this the critical town that exchanged hands some 15 times during the Civil War? One wonders why, as today, the place seems like such a small and forgotten place.

A few minutes outside Harper’s Ferry, the train moved past another handful of trainspotters. People who

take photos of trains in New York are considered terrorist risks, but in West Virginia, I’m sure terrorist concerns are the least of concerns.

Trainspotters way out there are genuine rail fans, and probably aren’t second guessed when they tell passersby they are taking photos of trains for fun. While renegade groups blew up railroad bridges leading to Harper’s Ferry during the Civil War, it is doubtful that this isolated corner of West Virginia will see action during the war on terror.

As we continued onward, the door continued to cause great stress on the many people who came across it and couldn’t figure out what to do. A family of four was trying to make their way to the sightseeing observation car when they came across the troublesome door.

Everyone in the group was very short. The father, with a knobby balding head, golf shirt and khaki shorts, could see through the door window that the crossover between the cars was extra bumpy as the train passed by some curvy sections.

The father told the family, in a semi-grave tone: “It’s too dangerous. We aren’t doing this.”

“But daddy, when can we go?” his son asked.

I think the real reason was that he couldn’t figure out how to open the door, but blamed the rough seas on the inability to pass through.

“Maybe we can go through tomorrow morning when it will be less bumpy.”

I wasn’t aware one could make train-car-stability predictions as if it was a Weather Channel boat and beach report. But the kid, though disappointed, seemed to buy it. The equally short mother was busy with the other kid looking out the side window at the passing landscape.

“Hon, what’s wrong? Why can’t we go through?”

“It’s too bumpy right now. We aren’t doing this.”

Through some sort of miracle gravitational force, the door slid open. The father, surprised, moved on through with his fam with ease to the next car.

The Sun Sets, And We’re a Long Way From Chicago. As the train approached Cumberland, Md., an announcement came over the public address system giving notice that the layover at western Maryland town would be the only chance to catch a smoke break.

Minutes later, Candice came through with a second warning about the smoke break. “Does anyone in this car smoke?”

It was an odd way of giving a second warning. She said it with such blunt force and intensity, as if she were on a doomed aircraft looking for a pilot to save the day and bring the craft back to earth. I think she really needed a smoke break.

Candice made her way through and went further down the car making the smoke break announcement.

“It seems like she’s encouraging it,” one fellow passenger behind me said.

The sun set when we left Cumberland and we were on our way through southwestern Pennsylvania. We lumbered through the hilly countryside and the landscape disappeared into wooded silhouettes. After the train pulled into Pittsburgh at 1:15 a.m., I decided to try to get some sleep. After we left Pittsburgh and made our way across Ohio, the train picked up speed. I vaguely remember pulling through Cleveland. I woke up as the sun was beginning to rise as we neared Sandusky. The train car was slowing awaking.

We crossed into Indiana by mid morning. At Elkhart, the largest city adjacent to northern Indiana’s Amish country, a whole crew of Amish boarded looking for a bank of seats. Millie was reading the latest AARP magazine with a chipper cover photo of Cybil Shepard when the sight of suspenders, long beards and bonnets took her eyes off of the magazine. Surely, if anyone would have trouble with the broken door, the technologically deficient Amish would freak out and wouldn’t know what to do.

But their fraternal leader easily slide the door open. And then, it shut on its own, as if the Amish had summoned the hands of the Almighty Savior to push the door shut behind them.

Immediately behind them were two women, one with crimped medium-length blond hair, a fluorescent diagonally multi-colored striped shirt and tight jeans. As she shuffled toward the door – she almost shimmied – showing her caboose off to Millie and the rest of the people around me eating a modest breakfast, she hit the door button. And of course, it didn’t open.

“Omigosh! It won’t open,” she said, turning to her friend.

She tried again. It didn’t open. A moping man, with an extreme buzzcut and bushy mustache followed behind them.

“It must have a bolt on it,” he said. He gave it a whirl and got the door open on his third attempt to slide it.

So it goes, the aura of cross-country train travel has lost its allure. Though I wasn’t necessarily in search of it in the first place, I knew that taking the train would present an interesting journey, despite being tired, groggy and feeling very dirty by the time wee arrived in Chicago.

Oddly enough, when the Capital Limited pulled into Chicago’s Union Station (an hour late, let me note), an aging steam locomotive pulling an historic array of decade’s old railcars with sightseeing passengers on some sort of rail-fan trip was pulling out of the station, destination: nostalgia. Photographers were lined up on a viaduct above the railyard documenting the departure.

As I saw the passengers inside that train pointing and taking pictures (one group even waved at us excitedly), I doubt they realized the journey we just had just completed.