L'ENFANT PLAZA: Can Children Save It?

L'Enfant Plaza, that monstrosity in Southwest Washington, could get a shot of badly needed redevelopment with the news that the Capital Children's Museum is headed for the I.M. Pei-designed government and hotel complex in a few years. The Washington Post reported Tuesday that the museum is closing its Capitol Hill location and will move to a new location in the complex in about four years, if everything goes according to plan.

But can children bring life to the drab collection of austere, minimalist, Cold War-era federal buildings? The District hopes so at least.

From the Post's Debbi Wilgoren and Dana Hedgpeth:

"L'Enfant Plaza needs help. It's all this stark, abandoned plaza," said D.C. Council member Jack Evans (D-Ward 2), whose district includes the site. "It needs some life to it. It needs to be a destination point for people."

But L'Enfant Plaza is already a destination ... for federal workers of second- and third-tier executive branch agencies. And they aren't necessarily the most uplifting bunch of souls to create a friendly destination for tourists.

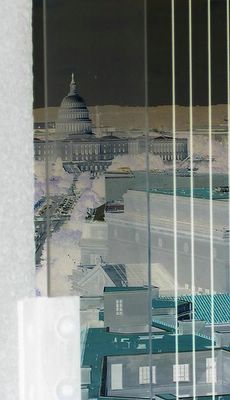

A Deserted Aztec Temple, With Thousands Trapped Inside. Southwest Washington was once a working class and commercial sector of the city near the waterfront. But urban renewal ... or literal urban removal ... essentially wiped the area off the map. (The building of the Southwest Freeway helped too.) The famed architect I.M. Pei designed the complex in the mid-1960s. But it isn't celebrated as some of his other designs are.

Anchored by the L'Enfant Promenade -- a boulevard that starts beneath the Energy Department and leads to an overlook of Interstate 395 and the Southwest Waterfront -- L'Enfant Plaza's stark piazzas seem to distribute any sort of modest pedestrian life over a wide swath of square footage. It is boxed in by the Loews hotel, the Energy Department, the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Postal Service. Part of it is elevated, cut off from the street grid, connected only by confusing staircases that lead to the imposing-but-deserted Aztec plaza before its Loews hotel altar.

Below ground, there is life in the "La Promenade" underground shopping plaza, albeit a depressing existence. For thousands of civil servants, it is the only lunch spot besides agency cafeterias. (I've heard that the Energy Department cafeteria isn't all that bad. Rumors of health code violations kept me away from the Department of Transportation cafeteria across Seventh Street.) Despite its "oooh la la" name, La Promenade might as well be named the Yuri Andropov Food and Retail Bazaar. When I was working in the area, there was persistent talk that the federal government subsidized the entire retail operation just so civil servants had the dignity to escape the dingy corridors of their offices for an hour every day.

Since I departed the federal government in January 2003, I haven't returned to La Promenade, so I may not be up-to-date as to what the retail corridor offers these days. When I was there, there was a Frank and Stein (with its 4 p.m. federal worker happy hour), an Au Bon Pain, at least three Asian pay-per-pound buffet establishments, a pizza place, Kelechi's African Authentics, a Dress Barn, a tie shop, a CVS and a McDonald's. This was all located below the plaza with no light, aside from a small glass pyramid that gave the Dress Barn and a coffee stand some natural daylight. The underground complex reminded me of the Martian colony in "Total Recall", filled with unhappy, worn out people trapped below ground.

Even the American Institute of Architects is reserved in its praise for the I.M. Pei design. From its guide to D.C. architecture (third edition):

Now a generation old, the first two office buildings here, fronting the north and south sides of the plaza, are generally regarded not only as sophisticated examples of design in concrete but also as technological innovations, for Pei integrated the mechanical and electrical systems into the exposed coffered ceilings, a practice by no means common on the 1960s. The complex, an outgrowth of the Zeckendorf-Pei plan for southwest Washington, maintains an air of quiet dignity, despite being located at an exit ramp of I-395.

Does it have dignity? Perhaps. Is is dead? Most definitely. (An appropriate reflection of the federal bureaucracy.)

Can It Be Saved? That is a good question. The Post doesn't really explore how the children's museum will fit into the complex. What L'Enfant Plaza needs is a dramatic overhaul. The government can't exactly bulldoze hundreds of thousands of square feet of office space. But the space could be reconfigured much in the way General Motors is renovating the Renaissance Center in Detroit. Both complexes have the same ailments: Big institutional buildings, cut off from the rest of the city by roads and elevated walkways, its human element trapped inside, confined to underground pedestrian precincts. By tearing down its huge bunker-like berms, the Renaissance Center is becoming more opened up to downtown Detroit. Opening up L'Enfant Plaza could be done in a similar fashion.

Despite L'Enfant Plaza violating everything Pierre L'Enfant stood for in his civic design, it can be helped, but it needs a major municipal and federal support. Getting busloads of children aren't going to solve L'Enfant Plaza's lack-of-humanity issues. My idea, which is probably unrealistic, would be to expand the commuter rail station at Seventh Street Southwest for Virginia Rail Express, creating more of a Boston-type North Station/South Station set-up for suburban rail commuters, alleviating pressure on Union Station. A second commuter hub for central Washington would really give Southwest Washington a needed shot in the arm. But until manholes stop exploding in Georgetown, the water system is free of lead, and children stop shooting each other in Southeast, a vibrant L'Enfant Plaza is just a pipe dream.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home